Josef Gočár: a prominent Czech architect

By Tracy A. Burns

One of the pioneers of modern Czech architecture, Josef Gočár carried out significant projects in Prague, Pardubice, and Hradec Králové, to name a few places, implementing styles of Cubism, Rondocubism, Functionalism, and Constructivism. His contributions to architecture between the two world wars have distinguished him as one of the most significant personalities in Czech architectural history. From the House of the Black Madonna in Prague to the development plan of modern Hradec Králové to the Grand Hotel in Pardubice, his awe-inspiring creations spectacularly dot the Czech landscape.

One of the pioneers of modern Czech architecture, Josef Gočár carried out significant projects in Prague, Pardubice, and Hradec Králové, to name a few places, implementing styles of Cubism, Rondocubism, Functionalism, and Constructivism. His contributions to architecture between the two world wars have distinguished him as one of the most significant personalities in Czech architectural history. From the House of the Black Madonna in Prague to the development plan of modern Hradec Králové to the Grand Hotel in Pardubice, his awe-inspiring creations spectacularly dot the Czech landscape.

From humble beginnings to star pupil

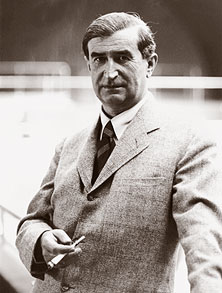

Josef Gočár was born in Semín near Přelouč, 18 kilometers from Pardubice, on March 13, 1880, at a time when the Czech lands were still subject to Austrian rule. His father was the owner of a brewery. In 1891 his family moved to the eastern Bohemia spa town of Bohdaneč. After completing his studies at the State Technical School in Prague, he attended the Prague School of Decorative Arts, where Czech architectural guru Jan Kotěra served as his mentor. The immensely talented Gočár even worked in Kotěra’s studio from 1906 to 1908. During 1904 he designed his parents’ tombstone in Bohdaneč and several apartment buildings in Hradec Králové. Before graduating, he went abroad to discover the architectural wonders in Belgium, Holland, and Germany. He joined the Mánes Union of Fine Arts but left it in 1911 to become the first chairman of the Cubist Group of Visual Artists. Then, in 1912, along with Pavel Janák and other architects, he founded the Prague Art Workshops for Cubist furniture.

Early projects

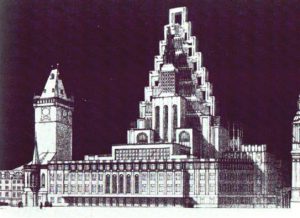

Although never realized, his design for Prague’s Old Town Hall featured a crystalline, tiered tower. His first major projects came to fruition in 1909 and 1910, when he built a staircase for the Church of the Virgin Mary on the main square in Hradec Králové. It connected the square to the peripheral road beneath the city walls. In 1910 he also designed the living quarters of a cavalry barracks in Bohdaneč, a construction of white brick that included a one-story building, two stables for horses, and a villa for the officers. His first significant project in Pardubice was carried out between 1909 and 1910 when he designed the Winternitz automated mill. From 1909 to 1911, he helped bring to life the Wenke department store in Jaroměř. He also worked on the editorial board of several magazines during this period.

Although never realized, his design for Prague’s Old Town Hall featured a crystalline, tiered tower. His first major projects came to fruition in 1909 and 1910, when he built a staircase for the Church of the Virgin Mary on the main square in Hradec Králové. It connected the square to the peripheral road beneath the city walls. In 1910 he also designed the living quarters of a cavalry barracks in Bohdaneč, a construction of white brick that included a one-story building, two stables for horses, and a villa for the officers. His first significant project in Pardubice was carried out between 1909 and 1910 when he designed the Winternitz automated mill. From 1909 to 1911, he helped bring to life the Wenke department store in Jaroměř. He also worked on the editorial board of several magazines during this period.

Converting to Cubism: The House of the Black Madonna

By 1912, the Čapek brothers, painter Václav Spála and sculptor Otto Gutfreund were just a few of the Czech artists who had converted to the Cubist style, which assembled shapes in abstract forms from many viewpoints. Gočár, along with Janák, joined them. In architecture, Cubism meant utilizing simple geometric shapes juxtaposed without illusions of classical perspective. That year he and Janák built one of the most impressive Czech Cubist structures and the first example of Czech Cubism in Prague – the reinforced concrete House of the Black Madonna with its Grand Café Orient on the corner of Prague’s Celetná street and Ovocný trh. The Baroque building designed in Cubist form does not interfere with the historical setting but instead complements it. The angular, bay windows, Baroque double roof, and Cubist ironwork on the balcony all contribute to the spell the building casts on downtown Prague. The third floor has flat windows and pilasters separated by Classical fluting. The stunning interior of the café – the oldest surviving Cubist interior in the world – also features Gočár’s furniture and chandeliers. In addition, this first-floor area has no supporting pillars. The building, declared a national monument in 2010, housed Czech Cubist artworks from October 1994 until October 2012.

By 1912, the Čapek brothers, painter Václav Spála and sculptor Otto Gutfreund were just a few of the Czech artists who had converted to the Cubist style, which assembled shapes in abstract forms from many viewpoints. Gočár, along with Janák, joined them. In architecture, Cubism meant utilizing simple geometric shapes juxtaposed without illusions of classical perspective. That year he and Janák built one of the most impressive Czech Cubist structures and the first example of Czech Cubism in Prague – the reinforced concrete House of the Black Madonna with its Grand Café Orient on the corner of Prague’s Celetná street and Ovocný trh. The Baroque building designed in Cubist form does not interfere with the historical setting but instead complements it. The angular, bay windows, Baroque double roof, and Cubist ironwork on the balcony all contribute to the spell the building casts on downtown Prague. The third floor has flat windows and pilasters separated by Classical fluting. The stunning interior of the café – the oldest surviving Cubist interior in the world – also features Gočár’s furniture and chandeliers. In addition, this first-floor area has no supporting pillars. The building, declared a national monument in 2010, housed Czech Cubist artworks from October 1994 until October 2012.

Rondocubism and the Legiobanka

When Czechoslovakia, born in 1918, was still an infant, Cubism went out of fashion, and Rondocubism became the new rave with decoration inspired by folk and nationalistic themes. Facades were adorned with circles and folkloristic characteristics, as artists attempted to create a new, national style. After serving in the army from 1916 to 1919, Gočár immersed himself in the Legiobank building on Prague’s Na Poříčí street. Four of its floors featured semi-circular half-columns with plastic ornamentation, and Cubist forms included the angular, bay windows. The hall itself blossomed with rich wall décor and decorative floor tiles as well as a stunning glass ceiling. Sculptors Gutfreund and Jan Štursa contributed to the sculptural ornamentation.

When Czechoslovakia, born in 1918, was still an infant, Cubism went out of fashion, and Rondocubism became the new rave with decoration inspired by folk and nationalistic themes. Facades were adorned with circles and folkloristic characteristics, as artists attempted to create a new, national style. After serving in the army from 1916 to 1919, Gočár immersed himself in the Legiobank building on Prague’s Na Poříčí street. Four of its floors featured semi-circular half-columns with plastic ornamentation, and Cubist forms included the angular, bay windows. The hall itself blossomed with rich wall décor and decorative floor tiles as well as a stunning glass ceiling. Sculptors Gutfreund and Jan Štursa contributed to the sculptural ornamentation.

Projects in Hradec Králové

It was around this time that Gočár began to gather more commissions in Hradec Králové, a city now dotted with his creations. During the early 1920s, he built the principal’s villa for the Koželuzská school, the Anglobanka building, and Rašín State High School with a gym and principal’s villa. He also repaired the facades of buildings on Masaryk square. During the era of Constructivism, which viewed art as a practice for social purposes, he continued to work there, designing the head-off ices of the State Railways, a reinforced concrete building with brick veneer and a Sluknov syenite outer coating on the ground-floor façade. During a 10-year period, he designed the town’s zonal development plan, the river regulation plan for the embankment, and the outer beltway system.

Gaining recognition

Gočár’s masterful constructions did not go unnoticed. In 1925 he received the Grand Prize for his design of the Czechoslovak pavilion for the World Exposition of Decorative Arts in Paris. The following year he received the French Order of the Légion d’Honneur. In 1924, shortly after Kotěra’s death, Gočár had been chosen to serve as a professor at the Academy of Decorative Arts in Prague. In 1928 he even became the school’s president.

Gočár’s masterful constructions did not go unnoticed. In 1925 he received the Grand Prize for his design of the Czechoslovak pavilion for the World Exposition of Decorative Arts in Paris. The following year he received the French Order of the Légion d’Honneur. In 1924, shortly after Kotěra’s death, Gočár had been chosen to serve as a professor at the Academy of Decorative Arts in Prague. In 1928 he even became the school’s president.

Turning to Functionalism

A year after this promotion, he made headway with Functionalism, which relied on the principle that architects should design a building exclusively for the purpose of that building. He planned the functionalist housing estate in Prague’s Baba area. Earlier, from 1927 to 1928, he had built the Church of Saint Wenceslas in Prague’s Vršovice district. He designed a number of other churches, too. His most significant functionalist project, though, was the Grand Hotel in Pardubice, created from 1927 to 1931. The four-story palace included several large halls for public events, a café, a bar, guest rooms, and offices as well as a movie theatre in the basement. Part of the façade was covered in bluish-grey platelets of opaque glass.

Death

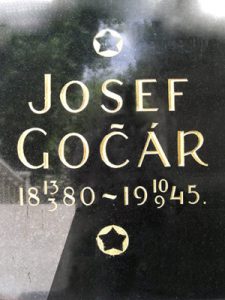

Gočár died in Jičín on September 10, 1945, and is buried in Prague’s Slavín Cemetery at Vyšehrad, along with other prominent historical figures. The remarkable and innovative creations of this architectural pioneer adorn the Czech landscape with their distinctive decoration.

Gočár died in Jičín on September 10, 1945, and is buried in Prague’s Slavín Cemetery at Vyšehrad, along with other prominent historical figures. The remarkable and innovative creations of this architectural pioneer adorn the Czech landscape with their distinctive decoration.