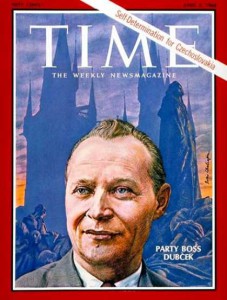

Alexander Dubček: The leader of the 1968 Prague Spring

By Tracy A. Burns

Alexander Dubček is best known as the Slovak First Secretary of Czechoslovakia who instigated the liberal reforms of the Prague Spring in 1968 when the country experienced more freedoms than it seemed destined to find its own individual identity while remaining a Communist country in what was called “socialism with a human face.” Yet he also was a prominent politician before 1968 and after the Velvet Revolution of 1989. His life ended tragically on November 7, 1992.

First years in democratic Czechoslovakia

Alexander Dubček was born November 27, 1921, in Uhrovec, nestled in the Strážovské Mountains of western Slovakia. He came into the world in the former home of the founder of the Slovak language, Ľudovít Štúr. At that time, independent and democratic Czechoslovakia was just over three years old. After many years of being subjected to Magyarization by the Hungarians in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, when the Hungarian language and customs were imposed, Slovaks finally experienced freedom and the right to express their own national identity in this democratic, multiethnic country governed by President Tomáš G. Masaryk. Before Alexander was born, the family had lived in Chicago, but his father refused to do military service because he was a pacifist. Yet Masaryk’s democratic ideals did not resonate well with Štefan.

Moving to the Soviet Union

When Alexander was three years old, his father moved the family to Kirghizia, now Kyrgyzstan, in the Soviet Union because he could not find work in Slovakia and because he was a communist. While Dubček studied in Gorkiy in 1937, for instance, he was treated as an outsider because the Soviets were not supposed to mingle with foreigners. There, Alexander saw the famine, watching people die in the streets. He also witnessed poverty and collectivization. Still, Alexander became intensely loyal to the Soviet Union. The family moved back to Czechoslovakia in 1938 when Stalin announced that all foreign residents in the Soviet Union must apply for Soviet citizenship or leave immediately.

Under Nazi rule

In 1939, the Nazis marched into Czechoslovakia and created the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia while Slovakia became a Nazi puppet state. Dubček joined the illegal Communist Party in Slovakia and was a member of the underground anti-Nazi resistance movement. In August of 1944, he fought against the Germans in the Slovak National Uprising, when he was injured. His brother, Július, was killed by the Nazis. Curiously enough, when Dubček was wounded, he was taken to the home of a fellow partisan, Anna Ondrišová, who would, in 1945, become his wife. The couple would have three sons – Milan, Pavel, and Peter.

Rising in the ranks

After the war, the popular Dubček received promotion after promotion. From 1951 to 1955 he was a member of the National Assembly, which was Czechoslovakia’s Parliament. In 1958 he became a member of the Central Committee of Czechoslovakia’s Communist Party and was re-elected to the Slovak Central Committee. From 1955 to 1958, he studied Communist management, economics, and ideology at the Higher Party School in Moscow. One of his classmates was Mikhail Gorbachev.

Political democratization, economic reform, and Slovak nationalism

During the early 1960s, Czechoslovakia experienced a serious economic decline. Slovaks were disgruntled with Prague’s centralism, and destalinization was not popular. Dubček rose in the ranks, although Czechoslovak President Antonín Novotný, a hard-liner, became his arch-rival. In 1962 Dubček became a member of the Czechoslovak Party Presidium. From 1963 he served as First Secretary of the Slovak branch of the Party. From 1960 to 1968, he was a member of Parliament. From 1964 to 1967 he was dismayed by the dogmatic procedures at the top levels of the Party apparatus, strongly disagreeing with the Party’s methods. The relationship between Dubček and Novotný became even more tense during the mid-1960s. Still, before 1968 Dubček saw the West in a very negative light and professed undying loyalty to the USSR. He believed that the betrayal of Munich and the war tied Czechoslovakia to the USSR. Dubček favored political democratization, economic reform, and Slovak nationalism. During the 150th anniversary of Štúr’s birth in 1965, Dubček embraced the creator of his mother tongue as a true hero, even though Karl Marx had condemned Štúr.

Replacing First Secretary Novotný

In October of 1967, Dubček and other reformers fervently opposed President Novotný at a Central Committee Meeting. Novotný was so incensed that he persuaded Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev to come to Prague in December of 1967, but his plan to discredit Dubček and other reformers worked against him. Brezhnev was not impressed with Novotný, acknowledging the lack of support for the president. In January of 1968, Novotný was forced to resign as First Secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party, and Dubček became the first Slovak to hold the highest position in the Party. During that month Dubček also traveled to Moscow to assure the Soviet Union that Czechoslovakia remained a faithful ally.

Implementing reforms during the Prague Spring

While Dubček remained loyal to Moscow and Communism, he wanted Czechoslovakia to embark on its own individual path while maintaining a socialist government. The country experienced liberal reforms that allowed writers to demand that the purge victims of the 1950s be rehabilitated and allowed social and political organizations to be free of Communist Party control. The April 5 Action Program described what came to be referred to as “socialism with a human face.” It demanded full equality in economic relations between Czechoslovakia and the USSR and urged the Soviets to take their advisors out of the country. Dubček and his followers wanted real elections for party officials with secret ballots. National minorities were represented in institutions, and strikes were legalized. Censorship was abolished on June 26, 1968, and a day later many newspapers published Ludvík Vaculík’s 2,000 Words proclamation, supporting reform and democratization.

While Dubček remained loyal to Moscow and Communism, he wanted Czechoslovakia to embark on its own individual path while maintaining a socialist government. The country experienced liberal reforms that allowed writers to demand that the purge victims of the 1950s be rehabilitated and allowed social and political organizations to be free of Communist Party control. The April 5 Action Program described what came to be referred to as “socialism with a human face.” It demanded full equality in economic relations between Czechoslovakia and the USSR and urged the Soviets to take their advisors out of the country. Dubček and his followers wanted real elections for party officials with secret ballots. National minorities were represented in institutions, and strikes were legalized. Censorship was abolished on June 26, 1968, and a day later many newspapers published Ludvík Vaculík’s 2,000 Words proclamation, supporting reform and democratization.

Failed attempts at negotiations

The Soviet Union was less than pleased. It tried to put a halt to the liberal reforms by means of negotiations. Dubček was summoned to Moscow, but he refused to go. Instead, the Soviets and Dubček met for negotiations at Čierná nad Tisou on the Slovak-USSR border. Although Dubček tried to reassure Moscow that the country remained faithful to Communist doctrine, the hard-liners did not back down. Dubček had been under the impression that he could continue to put reforms in place as long as he assured Moscow he was a loyal ally. Dubček was so incensed by the Soviet demands that he walked out of the meeting. At the second meeting in Bratislava, Dubček was pressured to assure the Soviet Union that his country remained loyal to the foundation of the socialist regime, a declaration that disappointed many reformers.

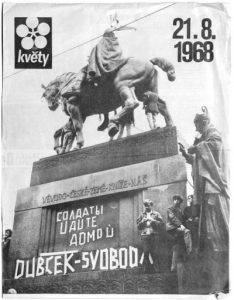

The Soviet Invasion

On the night of August 20-21 of 1968, 200,000 troops from the Warsaw Pact countries of the USSR, Poland, East Germany, Hungary, and Bulgaria entered the territory of their defenseless ally, as tanks crushed the liberal reforms of the Prague Spring in the largest military operation in Europe since World War II. Still, Dubček pleaded with his people not to use force against the Warsaw Pact soldiers. Brezhnev bullied Dubček and other reformers and even threatened to incorporate Slovakia into the USSR and to force Bohemia and Moravia to be autonomous under Soviet rule. Dubček was arrested by the Soviets and taken to Moscow.

On the night of August 20-21 of 1968, 200,000 troops from the Warsaw Pact countries of the USSR, Poland, East Germany, Hungary, and Bulgaria entered the territory of their defenseless ally, as tanks crushed the liberal reforms of the Prague Spring in the largest military operation in Europe since World War II. Still, Dubček pleaded with his people not to use force against the Warsaw Pact soldiers. Brezhnev bullied Dubček and other reformers and even threatened to incorporate Slovakia into the USSR and to force Bohemia and Moravia to be autonomous under Soviet rule. Dubček was arrested by the Soviets and taken to Moscow.

The Moscow Protocol

In Moscow on August 26, after he was threatened and suffered from fainting spells, Dubček signed the 15 doctrines of the Moscow Protocol, paving the way for the rigid era of normalization that would restore Communist order in Czechoslovakia. When Dubček came back to Prague a day after signing the document, he was still serving as First Secretary. Then, on March 21 and March 28, the Czechoslovak ice hockey team defeated the Soviet Union in the World Cup in Stockholm. Czechoslovak fans destroyed the offices of the Soviet airline Aeroflot and other Soviet institutions. Shortly thereafter, Dubček was forced to resign as First Secretary. But Dubček was not totally out of the picture – yet. He was re-elected to the Federal Assembly as Speaker. Then, between 1969 and 1970, he served as the country’s ambassador to Turkey, but he was not allowed to take his children with him. The Communists hoped he would emigrate, but he disappointed them again.

In Moscow on August 26, after he was threatened and suffered from fainting spells, Dubček signed the 15 doctrines of the Moscow Protocol, paving the way for the rigid era of normalization that would restore Communist order in Czechoslovakia. When Dubček came back to Prague a day after signing the document, he was still serving as First Secretary. Then, on March 21 and March 28, the Czechoslovak ice hockey team defeated the Soviet Union in the World Cup in Stockholm. Czechoslovak fans destroyed the offices of the Soviet airline Aeroflot and other Soviet institutions. Shortly thereafter, Dubček was forced to resign as First Secretary. But Dubček was not totally out of the picture – yet. He was re-elected to the Federal Assembly as Speaker. Then, between 1969 and 1970, he served as the country’s ambassador to Turkey, but he was not allowed to take his children with him. The Communists hoped he would emigrate, but he disappointed them again.

Expulsion

In 1970 Dubček was expelled from the party. From 1970 to 1985, he worked for the Forestry Service while still residing in his villa in a posh section of Bratislava. He did not take part in any dissident activities. In 1988 he was permitted to travel to Italy to accept an honorary doctorate from Bologna University.

During and after the 1989 Velvet Revolution

During the 1989 Velvet Revolution, Dubček was an avid supporter of the pro-democracy Public Against Violence and Civic Forum organizations. On November 24, he received applause from the crowd when he appeared with future president Václav Havel on the Melantrich building balcony overlooking Wenceslas Square. Dubček was on the stage of the Lanterna Magika theatre, which served as the Civic Forum headquarters, with Havel when the Communist Party officials resigned. He was even a candidate for president but was elected Chairman of the Federal Assembly on December 28, 1989, instead. He was re-elected to that post in 1990 and 1992. In 1992 he became the leader of the Slovak Democratic Party of Slovakia while serving on the Federal Assembly. Dubček mainly dealt with improving Czech and Slovak relations and foreign affairs. After it was announced in 1992 that Czechoslovakia was splitting into two states, Dubček refused to continue his political role, citing fear of a Slovak government controlled by autocratic Vladimír Mečiar. During the early 1990s, he received international recognition, too. In 1990 he was the recipient of the International Humanist Award from the International Humanist and Ethical Union, and that same year he gave the commencement address at The American University in Washington, DC, on his first visit to the States.

During the 1989 Velvet Revolution, Dubček was an avid supporter of the pro-democracy Public Against Violence and Civic Forum organizations. On November 24, he received applause from the crowd when he appeared with future president Václav Havel on the Melantrich building balcony overlooking Wenceslas Square. Dubček was on the stage of the Lanterna Magika theatre, which served as the Civic Forum headquarters, with Havel when the Communist Party officials resigned. He was even a candidate for president but was elected Chairman of the Federal Assembly on December 28, 1989, instead. He was re-elected to that post in 1990 and 1992. In 1992 he became the leader of the Slovak Democratic Party of Slovakia while serving on the Federal Assembly. Dubček mainly dealt with improving Czech and Slovak relations and foreign affairs. After it was announced in 1992 that Czechoslovakia was splitting into two states, Dubček refused to continue his political role, citing fear of a Slovak government controlled by autocratic Vladimír Mečiar. During the early 1990s, he received international recognition, too. In 1990 he was the recipient of the International Humanist Award from the International Humanist and Ethical Union, and that same year he gave the commencement address at The American University in Washington, DC, on his first visit to the States.

A tragic fate

But fate had tragic plans for Alexander Dubček. He was traveling in thick rain on a highway near Humpolec, Czech Republic at 9:00 am on September 1, 1992, when his driver was going too fast. Dubček, not wearing a seat belt, was thrown from the car. He died of his injuries on November 7 in a Prague hospital. He is buried in Bratislava’s Slávičie údolie Cemetery. In 2003 he posthumously received the Czech Republic’s Order of the White Lion award.

But fate had tragic plans for Alexander Dubček. He was traveling in thick rain on a highway near Humpolec, Czech Republic at 9:00 am on September 1, 1992, when his driver was going too fast. Dubček, not wearing a seat belt, was thrown from the car. He died of his injuries on November 7 in a Prague hospital. He is buried in Bratislava’s Slávičie údolie Cemetery. In 2003 he posthumously received the Czech Republic’s Order of the White Lion award.